Stow, Massachusetts

Stow, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

Town center of Stow | |

| Motto(s): "A place for growing up in and a place for coming back to" | |

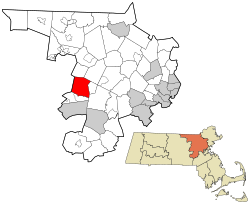

Location of Stow in Middlesex County, Massachusetts | |

| Coordinates: 42°26′13″N 71°30′22″W / 42.43694°N 71.50611°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Middlesex |

| Settled | c. 1660 |

| Established | 1669 |

| Incorporated | May 16, 1683 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Open town meeting |

| • Town Administrator | Denise Dembkowski |

| Area | |

• Total | 18.1 sq mi (46.9 km2) |

| • Land | 17.6 sq mi (45.6 km2) |

| • Water | 0.5 sq mi (1.2 km2) |

| Elevation | 231 ft (70 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 7,174 |

| • Density | 407.6/sq mi (157.4/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Code | 01775 |

| Area code | 351 / 978 |

| FIPS code | 25-68050 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0618236 |

| Website | www.stow-ma.gov |

Stow is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. The town is located 21 miles (34 km) west of Boston, in the MetroWest region of Massachusetts. The population was 7,174 at the 2020 census.[1] Stow was officially incorporated in 1683 with an area of approximately 40 square miles (100 km2).

Over centuries it gave up land as newer, smaller towns were created, ceding land to Harvard (1732), Shirley (1765), Boxborough (1783), Hudson (1866) and Maynard (1871). Stow now has an area of 18.1 square miles (47 km2). With the exception of factories at Assabet Village and Rock Bottom (later Maynard and Gleasondale), Stow was primarily sparsely settled farm and orchard land until the 1950s.

History

[edit]Previous to its incorporation in 1683, Stow was called Pompositticut Plantation.[2] Stow was officially incorporated in 1683.[3] The earliest Colonial settlers, c. 1660, were Matthew Boon and John Kettell, who settled the land of Tantamous (Jethro), a Native American, whose land was called "Pompocitticut." Boon settled by a pond (later bearing his name: Lake Boon) with a vast tract of land surrounding him. It is said that he traded all this for a single jackknife. A monument bearing his name is located on the plot of land where he formerly resided. John Kettell took up residence in a portion of land in the southwestern corner of Stow where another monument marks the alleged site of his farm. Both families were affected by King Philip's War, an attempt by Native Americans to drive out colonists. Boon and Kettell were killed. Their families had been moved to other locations, and survived. The area that was to become Stow was not resettled by colonists for several years.[4][5]

The original development of Stow—a mile east of the current center, became known as Lower Village after a meeting hall, and later, churches, were built to the west. The old cemetery on Route 117/62 is officially Lower Village Cemetery.[4] On October 28, 1774, Henry Gardner, a Stow resident, was elected Receiver-General of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, the government of Massachusetts during the American Revolution. After the war, Gardner served as state treasurer. Gardner's grandson, also Henry Gardner, was the governor of Massachusetts from 1855 to 1857.[6]

As with many colonial era Massachusetts towns, Stow started with a large area and gave up land as newer, smaller towns were created. Stow ceded land to Harvard (1732), Shirley (1765), Boxborough (1783), Hudson (1866) and Maynard (1871). Stow lost 1300 acres (5.3 km2) and close to half its population to the creation of Maynard. Prior to that, what became Maynard was known as "Assabet Village" but was legally still part of the towns of Stow and Sudbury. There were some exploratory town-founding efforts in 1870, followed by a petition to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, filed January 26, 1871. Both parent towns opposed this effort, but state approval was granted April 19, 1871. The population of the newly formed town—at 1,820—was larger than either of its parent towns.[7] In return, the new town paid Sudbury and Stow about $23,600 and $8,000 respectively. Sudbury received more money because it owned shares in the railroad, the wool and paper mills were in Sudbury, and more land came from Sudbury.[7]

In 1942 the U.S. Army seized about one-tenth of the town's land area, from the south side, to create a munitions storage facility. Land owners were evicted. The land remained military property for years. In 2005 it became part of the Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge.[8][9]

The modern butternut squash was developed by Charles Leggett in Stow in 1944;[10] the Leggett Woodlands in the town are named after his family, after his wife donated the land.[11][12] The squash was developed in a field across from the woodland.[12]

On New Year's Day, 1984, Kevin Walsh took off from Minute Man Air Field with 57 helium balloons tied to a lawn chair, later descending by parachute. He was cited with four violations of FAA regulations and fined $4,000 ($10,922.66 adjusted for inflation to 2022).[13] He reached an altitude of 9,000 feet (2,700 m).[14][15]

As of 2022, Stow is one of the only municipalities in Massachusetts not to have a Dunkin' Donuts, after the two in town closed down that year, for which the town received attention on social media.[16][17]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 18.1 square miles (47 km2), of which 17.6 square miles (46 km2) is land and 0.5 square miles (1.3 km2) (2.60%) is water. It is located in eastern/central Massachusetts.

Major bodies of water are Assabet River, Elizabeth Brook, Lake Boon, White's Pond and Delaney Flood Control Project, in the northwest corner. The Assabet River flows through Stow from west to east, spanned by three bridges. Average flow in the river is 200 cubic feet per second. However, in summer months the average drops to under 100 cfs. The flood of March 2010 reached 2,500 cfs. Recent, monthly and annual riverflow data—measured in Maynard—is available from the U.S. Geological Service.[18]

Gleasondale

[edit]The village of Gleasondale is in both Hudson and Stow. Gleasondale was originally known as Randall's Mills, and then later became known as Rock Bottom. The name "Rock Bottom" came about after a workman struck a solid rock while digging the mill's foundations and a coworker cried out, "You've struck rock bottom!" The name was changed to Gleasondale in 1898 after two of the original mill owners, Mr. Gleason and Mr. Dale.[6] An 1856 map[19] shows Assabet as a village on the eastern border – this became the center of the Town of Maynard in 1871.

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 1,455 | — |

| 1860 | 1,641 | +12.8% |

| 1870 | 1,813 | +10.5% |

| 1880 | 1,045 | −42.4% |

| 1890 | 903 | −13.6% |

| 1900 | 1,002 | +11.0% |

| 1910 | 1,115 | +11.3% |

| 1920 | 1,101 | −1.3% |

| 1930 | 1,142 | +3.7% |

| 1940 | 1,243 | +8.8% |

| 1950 | 1,700 | +36.8% |

| 1960 | 2,573 | +51.4% |

| 1970 | 3,984 | +54.8% |

| 1980 | 5,144 | +29.1% |

| 1990 | 5,328 | +3.6% |

| 2000 | 5,902 | +10.8% |

| 2010 | 6,590 | +11.7% |

| 2020 | 7,174 | +8.9% |

| 2022* | 7,042 | −1.8% |

| * = population estimate. Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30] | ||

As of the census[31] of 2018, there were 7,214 people, 2,575 households, and 2,090 families residing in the town. The population density was 380.6 inhabitants per square mile (147.0/km2). There were 2,526 housing units at an average density of 143.5 per square mile (55.4/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 91.8% White, 2.7% African American, 0.2% Native American, 3.9% Asian, 0.4% from other races, and 1.9% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.8% of the population.

There were 2,575 households, out of which 25.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 69.7% were married couples living together, 2.2% had a male householder with no wife present, 6.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 21.7% were non-families. The householder of 17.4% of all households were living alone and 16.7% was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.75 people and the average family size was 3.10 people.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 28.2% under the age of 20, 24.6% from 20 to 44, 34.5% from 45 to 64, and 12.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 43.5 years. For every 100 males there were 103.1 females. For every 100 males age 18 and over, there were 106.8 females.

As of 2015, the median income for a household in the town was $137,551, and the median income for a family was $153,763. The per capita income for the town was $51,081. About 2.7% of families and 4.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 4.7% of those under age 18 and 3.1% of those age 65 or over.

Points of interest

[edit]Golf

[edit]Stow is known for its four golf courses (81 total holes). The best known of these is Stow Acres Country Club (36 holes), the site of the 1995 US Amateur Public Links Championship.

The south course, formerly known as Mapledale Country Club, hosted a nine-hole course that was the first course designed, operated, and managed by a Black man, Robert H. Hawkins. Hawkins bought the property in 1926, and it was home to the first three United States Colored Golf Association (USCGA) Opens from 1926-1928.[32]

Apple orchards

[edit]Stow is also well known for its apple orchards (Carver Hill, Small Farm, Derby Ridge Farms, Honey Pot Hill, One Stack Farm and Shelburne Farms), which provide tourism for the town in the fall.

Town Center

[edit]The town center contains a memorial for the Stow soldiers lost in the French and Indian War, Revolutionary War, both World Wars, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the various U.S. involvements in the Middle East. Townspeople gather at the site on Memorial Day.[33]

Near the Randall Library (named after John Witt Randall[34]) is a trolley station from when the town was connected by trolley line to Boston and Waltham.[35]

Assabet Wildlife Sanctuary

[edit]A significant portion of the Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge (opened in 2005) is located in Stow.

American Heritage Museum

[edit]A military history museum built in 2018 and located on the grounds of the Collings Foundation, with a large collection of tanks and other artifacts from World War I, World War II, the Korean War, Vietnam War, Gulf War, Iraq War, the September 11 attacks and its ensuing War on Terrorism.[36]

Pine Bluffs

[edit]Pine Bluffs is a 34-acre park and beach located off Sudbury Road on the northern shore of Lake Boone.[37] It underwent renovations in 2017–2018 to have a pavilion, restrooms, and be more accessible.[38] The forest nearby contains many trails including well as a dropoff for launching canoes and kayaks, and contains a tire swing overlooking the lake as well as a popular hill that locals have parties at.[39]

Notable people

[edit]- Matthew Tobin Anderson, known as M. T. Anderson, an author primarily of picture books for children and novels for young adults; he currently lives in Cambridge, MA[40]

- Ethan Anthony, attended public schools in Stow, architect[41]

- Tom Barrasso, former NHL goaltender, grew up in Stow, played high school hockey for Acton-Boxborough, and went directly from high school to NHL

- Dan Duquette, former general manager of the Montreal Expos and Boston Red Sox and current general manager (2011–present) with the Baltimore Orioles

- Chris Fleming, Stand-up comedian and YouTuber

- Henry Gardner Sr., first receiver-general/state treasurer of Massachusetts from 1774 until his death in 1782. His grandson Henry J. Gardner served as governor from 1855 to 1858

- Kate Hogan, Massachusetts State Representative for Third Middlesex District since January 2009

- Grace Metalious, of "Peyton Place" fame. Her husband taught school in Stow after moving from Gilmanton, New Hampshire, where they had lived while she wrote her book; it is not clear whether she ever lived in Stow, as biographies state that they separated about the time the book was published

- Lee H. Pappas, publisher of high-tech publications, including ANALOG Computing, PC Laptop, VideoGames & Computer Entertainment, and TurboPlay

- Samuel Parris, Puritan minister who preached in Stow during the summer of 1685 and later played a role in the Salem witch trials

- John Witt Randall, poet, naturalist, and art collector

- Jeremy Reiner, chief meteorologist for WHDH (TV)[42]

- George P. Shultz, former U.S. Secretary of State (1982–1989), lived in Stow when he was teaching at MIT[43]

- Patricia Walrath, former Massachusetts State Representative (1985–2009) for Third Middlesex District, before that a Stow Selectman

- Austin Warren, literary critic, author, and professor of English

Government

[edit]Stow uses the Open Town Meeting form of town government popular in small to mid-sized Massachusetts towns. Anyone may attend a town meeting, but only registered voters may vote. Before the meeting, a warrant is distributed to households in Stow and posted on the town's website. Each article in the warrant is debated and voted on separately. Stow does not require a defined minimum of registered voters to hold a town meeting and vote on town business, i.e., zero quorum. Important budgetary issues approved at a town meeting must be passed by a subsequent ballot vote. Stow's elected officials are a five-member Board of Selectmen. Each member is elected to a three-year term. Also filled by election are the School Committee, Housing Authority, Randall Library Trustees and a Moderator to preside over the town meetings. Positions filled by appointment include the Town Administrator and other positions.

-

Stow Town Hall

-

Stow Town Hall historical plaque

State and federal government

[edit]On the federal level, Stow is part of Massachusetts's 3rd congressional district, represented by Lori Trahan. The state's senior (Class I) member of the United States Senate is Elizabeth Warren. The junior (Class II) senator is Ed Markey.

Schools

[edit]Stow is a member of the Nashoba Regional School District, also serving the towns of Lancaster and Bolton. Stow is home to The Center School (Pre-K–5) and Hale Middle School (6–8).

Stow also contains the "Stow West School", a one-room schoolhouse that was in operation from 1825–1903.[44]

Pompositticut School (an elementary school, K–3) was converted into a community center in 2017.[45]

Massachusetts Firefighting Academy

[edit]Stow is home to the headquarters of the Massachusetts Firefighting Academy, which provides recruit and in-service training for Massachusetts firefighters.[46]

Airports

[edit]- Minute Man Air Field (6B6) is a privately owned, public-use airport

- Crow Island Airport is a privately owned airfield for ultralights

- The Collings Foundation has a small grass airstrip adjacent to their museum

Footnote

[edit]- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Stow town, Middlesex County, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "Welcome to the Town of Stow | Stow MA". www.stow-ma.gov. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ Fuller, Ralph. (2009). Stow Things. Stow Historical Publishing Company.

- ^ a b Childs, Ethel B. (1983). History of Stow. Stow Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-9611058-1-5

- ^ Crowell, PR (1933). "Stow, Massachusetts 1683-1933" (PDF). Town of Stow, Massachusetts. Retrieved September 19, 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Lewis, Halprin; Sipler, Barbara (1999). Images of America: Stow. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. pp. 7, 36. ISBN 0752412914. OCLC 947956885.

- ^ a b Sheridan, Ralph (1971). A History of Maynard 1871-1971. Town of Maynard Historical Committee.

- ^ "Refuge website: About the Refuge". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

- ^ "Friends of the Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge". www.farnwr.org. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ Ryan, Janine (September 21, 2013). "The strange history of the butternut". Farmer's Weekly. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ^ "Leggett Woodland". Stow Conservation. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ a b "Leggett Fairy Trail". Gaining Ground - Land Protection Blog. May 21, 2020. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Did a Man Fly in a Lawn Chair Attached to Helium Balloons?". Snopes.com. December 21, 2000. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ^ "History and Technical Notes". www.clusterballoon.org. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ^ CERULLO, MAC (June 6, 2018). "Balloon traveler Kevin Walsh writes book on his great adventure". Homenewshere.com. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ "Stow, Mass., lost its two Dunkin's, becoming a 'Dunkin' desert'". www.boston.com. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ^ Oemig, Jennie. "Where to get coffee? 1 MA town had its Dunkin' stores close, what it means for local cafes". Wicked Local. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ^ USGS Current Conditions for USGS 01097000 ASSABET RIVER AT MAYNARD, MA. Waterdata.usgs.gov. Retrieved on July 17, 2013.

- ^ "Excerpt from the Map of Middlesex County, Massachusetts 1856: STOW".

- ^ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "City and Town Population Totals: 2020−2022". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ Melia, Sean (February 22, 2022). "The story of Robert Hawkins and Mapledale Golf Club". AmateurGolf.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Stow, Massachusetts. "Stow Memorial Day Parade and Ceremonies". Stow, Massachusetts. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ "About the Library | Stow MA". www.stow-ma.gov. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ Red Book,: Interstate Automobile Guide, New England. F. S. Blanchard and Co. 1905.

- ^ "The Collings Foundation - Preserving Living Aviation History". The Collings Foundation. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Pine Bluff Beach - Stow - MA - Massachusetts Trails". www.mass-trails.org. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Pine Bluffs Recreational Area on Lake Boon - Kids Outdoors". kids.outdoors.org. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Park Rules & Regulations - | Stow MA". www.stow-ma.gov. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Profile: Author M.T. Anderson Challenges Young Adults With Complex Narratives", The Washington Post, November 29, 2008.

- ^ "Ethan Anthony | INTBAU". Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ^ "Jeremy Reiner of Stow watches the weather".

- ^ "Secretary Shultz Takes Charge". Short History of the Department of State. United States Department of State, Office of the Historian. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ "One Room Was Enough: Stow West School Museum". www.thehistorylist.com. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Pompositticut Community Center | Stow MA". www.stow-ma.gov. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ The Massachusetts Firefighting Academy

Further reading

[edit]- Gordon Stow Carvill, The Stow Family of Stow, Massachusetts. Englewood, CO: G.S. Carvill, 2003.

- Preston Crowell and Olivia Crowell, Stow, Massachusetts, 1683-1933: Compiled in Honor of the Two Hundred Fiftieth Anniversary of the Town. Stow, MA: Rev. and Mrs. Preston R. Crowell, 1933.

- Samuel Adams Drake, History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts: Containing Carefully Prepared Histories of Every City and Town in the County. In Two Volumes. Boston: Estes and Lauriat, 1880. Volume 1 | Volume 2

- Lewis Halprin, Stow, Massachusetts. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 1998.

- D. Hamilton Hurd, History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts: With Biographical Sketches of Many of its Pioneers and Prominent Men. In Three Volumes. Philadelphia, PA: J.W. Lewis & Co., 1890. Volume 1 | Volume 2 | Volume 3

- Robert H. Rodgers, Middlesex County in the Colony of the Massachusetts Bay in New England: Records of Probate and Administration, February 1670/71-June 1676. Rockport, ME: Picton Press, 2005.

- Vital Records of Stow, Massachusetts, To the Year 1850. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1911.